COMMENTARY

This commentary is intended to include additional information relevant to the works included in the portfolio. It discusses the processes used and the inspiration behind the works in order to gain a more holistic view of my techniques and motivations.

Cromlech - Trumpet Concerto

This work took a long gestation period to reach the initial stage of sketching the introduction. I had clearly in my minds ear the idea of a building force leading into a vast austere landscape. I also new that there was to be a clear dialogue between the Harp and the Trumpet. I attempted to create a work from a single pitch, an idea borrowed from Adorno, and therefore I began to study the harmonic series that the Trumpet is solely dependant upon. This produces a series via a first-time sieve (removing any repeated pitches regardless of octaves) that can then be used to produce a transposition matrix. Another result of this set was the generation of an almost octatonic scale. After the initial introduction the next 76 bars presents the magic square of the first movement in the Flute and the Bassoon - in retrograde - whilst at the same time building up dramatic tension through its sustained nature that is then released into a fast and furious first movement.

The meaning of gestation period for myself is derived from a personal belief that composition exists on several levels in the human psyche. The first stage of a composition is that of the development of the initial 'inspiration', when the idea first presents itself, and this can take several forms that differentiate between the levels of the human psyche that I have mentioned. On one level the 'inspiration' is a subconscious realisation of a musical idea - usually a vague presentation of the idea of the work as a whole, on another level it may present itself as a very conscious resolution to a particular problem - musical or otherwise, and finally it may appear as a series of perceived influences (external visual or aural sources) that permeate the mind and result in the production of a 'feel' for the work. All of these mental levels (contexts) for the preparation of a work usually combine in differing quantities, and therefore in differing levels of conscious and subconscious thought, until there is a 'creative spark' that ignites all of this mental activity to reveal the essence of the music to be created. The 'creative spark' is usually a totally subconscious and unexpected event, for example Robert Saxton, in an article in 'Composition Performance Reception' (ed. Thomas (1998) Ashgate), gives several instances of the 'creative spark' from persons including leading mathematicians. His point is that at the forefront of all academia and art there is the necessity to be creative to be able to arrive at the required solution. Without this creative ability we are nothing more than complex machines functioning to complete a task. A complex machine requires a set of rules to govern its performance and instructions to follow certain criteria, and at the forefront of any discipline these rules do not apply, which renders the complex machine useless. Universities are therefore the boiling pots of knowledge and creative energy, the essential ingredients in the advancement of any area of human endeavour and discovery. Perhaps it is this very point that is the main argument why composition should be and remain to be an academic subject; composers have always attempted to push forward the edge of the known musical sound world, much in the same way as academics are constantly pushing forward the boundaries of music knowledge.

The gestation period is therefore the time it takes for the conscious and subconscious mind to develop material and images until the 'creative spark' allows the composer to realise these images. The 'creative spark' may then be thought of as the point when subconscious becomes conscious thought. At this point of the compositional process a set of rules has been created, and in this instance they are that the work will be approximately seventeen minutes long, in three major sections, and be based upon the fundamental of all sound, the harmonic series. There is also a sense that the introduction should feel like it is groping for a musical idea and tonality, very much in the same fashion as the opening to Haydn's Creation, before the trumpet declamatorily proclaims the beginning of a ritual with an off stage trumpet fanfare. At this point we have enough information to start the complex machine. As Saxton points out in 'Composition Performance Reception' the less we think about everyday processes the more the human mind is capable of, less is more - so to speak, and in a similar fashion I use several devices so as to reserve thought for the larger musical issues and decision making. These devices include the magic square, proportional divisions for structure, and pitch generation techniques as can be illustrated from a recent work 'Structura Allegra'.

Structura Allegra was written specifically for performance by the Nossek String Quartet under the guidelines set out for the course of M.Mus / Ph.D at the University of Bristol. The specifications were to compose a work for string quartet of approximately ten minutes in length to be performable after one hour of rehearsal and workshop time.

In an attempt to avoid the loaded history of the genre without resorting to a plethora of gimics, harmonics and aleotoric tricks, I decided on a personal language that does not diverge too greatly from that of composers already known. I had been studying Bartók's Fifth Quartet quite closely and a hint of his musical language had already begun to permeate my own; that is not to say that any attempt was made at Bartók pastiche. The solution was to use as a starting point a music that was already referential and its sound world well known, this would absorb both the musicians and the audience in a known music before embarking on new but related material. I therefore returned to an idea that I had explored in a work many years before for brass quartet. The original music that is presented in the opening of the work is taken from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book (Fitzwilliam Museum Music Manuscript 168.) - P. 12, Vol.2 of the current edition.

Figure 1

|

Several commentators have suggested explanations for the work, for example Caldwell labels it as a basic plainsong setting, however it was Maxim's idea that it could be a sketch for a larger work that provided the initial inspiration for this and the earlier work.

The tenor line of CXI is taken from the Alleluia portion of the Felix Namque (see figure 2), a setting of the Felix Namque by Tallis proceeds CXI in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book. An eight-note incipit is taken from this plainsong and is subjected to some alterations to produce a more interesting and useful set.

Figure 2 Alleluia portion of the Lady-Mass Offertory, Felix Namque.

|

Figure 3 Transformation of eight-note incipit

|

This series [0, 2, 1, 5, 4, 3, 11, 0] above in Figure 3 is then used to produce the following matrices: (numbers in superscript represent a standard labelling of the pitches in sequence (1 through 64) that are used to reorder the pitches during the transformation through the magic square. For example the first number in the magic square of mercury (Table 2) is 8, therefore the eighth pitch of Table 1, 0 or C, becomes the first pitch of Table 3.)

Table 1 Pitch matrix (transformational square)

|

Table 2 Magic Square of Mercury

|

Table 3 New Matrix formed by projecting Table 1 through Table 2 Magic Square of Mercury.

|

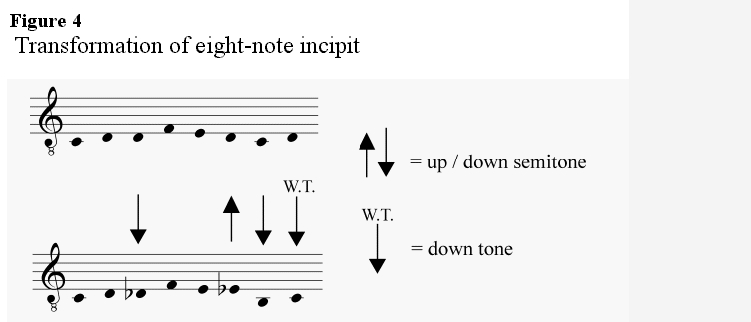

Figure 4 resulting pitches of the above procedure

|

Therefore a series of varied pitches are produced from a basic modal set to give the building blocks of the rest of the composition. The Violin I melody in bars 15 through 25 presents the first three lines of the new matrix (Table 3) and illustrates the pitch variation possibilities of this process Figure 5:

Figure 5 resulting pitches of the above procedure

|

Cromlech uses a similar device to generate the quasi-octatonic scale that dominates the work and can be heard from the very opening. However, in Cromlech the application of the procedure is less strict. The 'machine' had a tendency in previous works to take over the creative thinking - the process that it was meant to enhance the music by producing the raw material to allow the composer to make the more important musical and structural decisions.

The Blaina Overture is essentially an abstract realisation of the history of my home village. It is based on a hymn tune that was the favorite of the works dedicatee, and functions as an indication of the Church's constant significance in the area. The main source for the research behind the work is included as a link from the Blaina Overture page and was written by David James. Not much is known about the author and his research, which has few footnotes and an unusual bibliography, however, it does give a reasonable explanation of the areas history and outlines a period of rural activity before three periods of industrial activity, punctuated by depression caused by strikes, marches, and redundancies.

The works structure depends a great deal upon the divisions of the positive and negative golden section. These proportions of 0.618 and 0.382 of the whole can be seen throughout nature and have been well documented in the works of Bartok, particularly in his fifth string quartet.

The overall layout of the fifth string quartet appears to be constructed with the use of both Golden Section and Symmetrical proportions. As we can see (figure 5), the use of the division of the whole into a half and then quarters ( ---- lines) is essential to the placing of the golden section divisions. The half division occurs at bar 62, beat 2, of the scherzo. The Viola sounds an A / C dyad that completes the Scherzo section in augmentation in the next three bars. This held dyad effectively ends the rhythmic momentum of the section and could also be considered as superfluous to our consideration of the structure. The half division is therefore clearly presented by the short Viola dyad and can also be seen to have strong associations with the beginning of the Trio Section: the percentage difference from the start of the Trio is 0.005 and could therefore be considered accurate.

Figure 6 Graph of proportions in Bartoks Fifth String Quartet

The measurements are based on Bartók's annotations on the score and can therefore be said to be correct and intended by the composer. The numbers in parenthesis next to the divisions are the difference, in percentage, from the actual calculation; e.g. +ve G.S. (0.021) = 2.1% from the actual position of the golden section or division. This is calculated by dividing the difference of the actual time and the theoretical time by the whole. This figure gives an indication of the accuracy of the structure with respect the whole, rather than the amount of seconds. The benefit of defining inaccuracies as a percentage is that they are represented in the correct context.

The Blaina Overture attempts to ulitise these proportional techniques to produce an unusual form for the Brass Band 'test piece' genre. Apart from the structure the use of the different styles are also intended to be adventurous within the genre. Here, the initial opening figure represents great change and the first recorded instance of this was the invasion of the Romans - the nearby mountain Milfrean (literally a thousand crows) apparently got its name from the sight of the Roman Legions marching over the mountain with their golden eagle banners being mistaken for crows by the local inhabitants. This is then proceeded by the hymn tune presenting the foundation of St. Peter's Church and a further development of this represents the "The upheavals and sinkins and glens and koomes were more numerous in Aberystruth than in any other Parish" (Edmund Jones in "A Geographical, Historical and Religious Account of the Parich of Aberystruth, in the County of Monmouth. To which are added Memoirs of several Persons of note, who lived in the said Parish".)

Every element of the work and its subsequent Industrial and Depression sections is derived from the hymn tune and the procedures discussed above. The works duration c. 10 minutes was a stipulation of the commissioners and was though to be an adequate duration for a modern test piece.

Mari Lwyd - Music for Chamber Orchestra

Mari Lwyd is an ancient pagan custom in Wales and has recently seen a spate of attempts to revive the custom since its demise in the early part of the twentieth century.

Vernon Watkins' ballad, that I stumbled across many years ago in the library in LLanelli, was the main inspiration behind this work. Another version exists for chamber ensemble and was written for the P. M. Ensemble, however, even when writing that work an orchestral version was always playing at the back of mind. When Nick Little came and asked if I knew of a work for Chamber Orchestra that was a showcase for the wind and brass but involved little work for the strings I jumped at the chance to suggest that I could write a new work for him: the Mari Lwyd subject was particularly significant as this new work was intended for the Christmas concert.

Mari Lwyd is based solely on a tune recorded at one of the eisteddfodi in Llangollen in 1924. It is unusual as it has some awkward intervals and can be heard in its original form at the Chaos section of the work (figure 7) in canon played by the off stage brass. This work is created from this material using the processes above and some more leanient transformation procedures such as used in Strutura Allegra.

Figure 7 Off Stage Brass from Exodus - Mari Lwyd

|

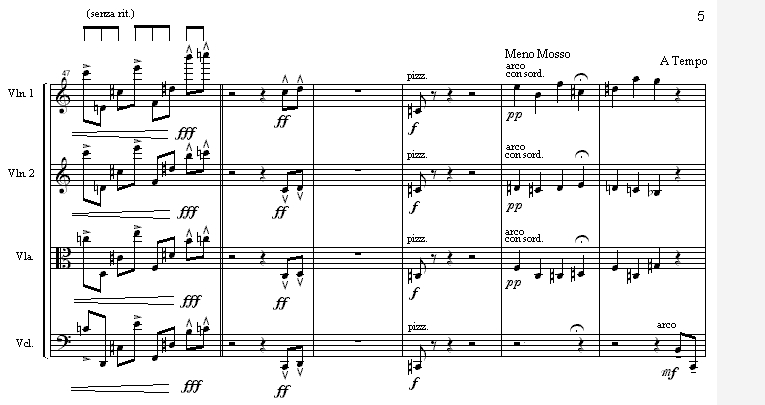

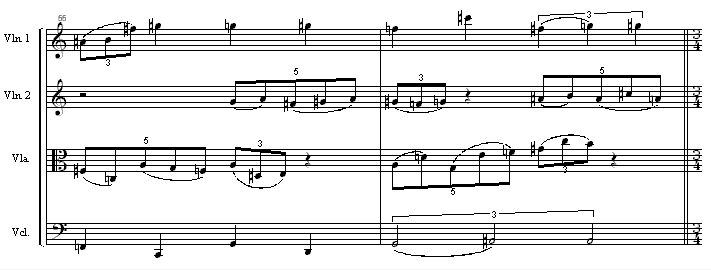

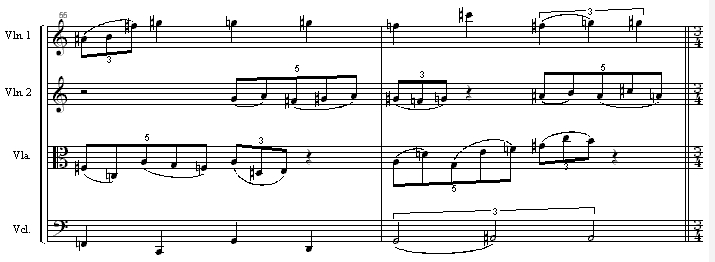

The 'transition section' of Strucctura Allegra (bars 48-57 - figure 8) is a very literal transition moving from the original set to a new variation of the set with an associated magic square. From the Meno Mosso in bar 51 a transformation or metamorphosis of the original set takes place through a process of addition and subtraction of interval classes (Table 4):

Table 4 Addition / subtraction table

|

The transformation is altered to give further variety to pitch, disguise the process and correct unsatisfactory results. The realisation of this can be seen in Figure 8. Whether or not the listener is aware of this process is beside the point, however, its presence and significance in the motion from the old matrix to the new is of paramount importance to my sense of logic.

Figure 8 Strucctura Allegra bars 48-57

|

|

|

All of the works in this project are essentially about nature and organic design of material. The development processes that I utilise are all attempts to maximise the potential of the material that I create or discover. The aim of this commentary has been to enlighten the reader in the techniques and methods of my music and to give some indication of how these works were constructed. It also aims to discuss some of the more inspirational elements of the compositional procedure without becoming a full analysis. A proper analysis is impossible, as the composer can never offer a level of subjectivity on which to provide a valid critique of his own music. I hope, therefore, that this commentary has brought to the attention of the reader aspects and insights that would have otherwise remained unknown.